I was supposed to become an architect. In grade twelve, I took an architectural design course, which introduces people to the studies of construction and design, allowing firsthand experience using CAD software and blueprint planning. I graduated with the highest overall grade that year, although I already knew I was not going to become an architect.

Instead, I had my sights of going to a college in a small city 10 hours north of where I called home, to learn about outdoor recreation and parks, a field of study that would have seemed fictional to me only a year earlier.

The realization came to me that architecture would never become a real career to me when I saw my grade eleven physics mark sit well below a 70%. Mathematics had a similar story. With scores that low, I wouldn’t be able to design sheds with any sort or real-world credentials, let alone homes which were my greatest architectural fascinations at the time.

I was really good at making up designs for homes. They were my dream homes that I would imagine in my head, that someday I would own. Some would be modest, but a few outlandish, as my dreams would curate different scenarios of the possible lives I would potentially be living. But ultimately, this was a big step in developing my creative muscle.

As a visual person, I would pick up on things I saw in the real world, and in media too, to replicate it for my pure enjoyment as a child and adolescent. It started when I was a young boy, designing my own mini cities in my bedroom, forming city streets, building homes, shopping centres and other buildings with wooden blocks, and then simulating the world by playing with Hot Wheels and Matchbox cars, creating fictional story lines all in my imagination. From one day it would be a quiet residential neighbourhood, the next a busy highway adjacent to a shopping mall, and then a farm the following, all from just recreating how I saw the world.

Looking out the window in any moving vehicle, whether that’d be a car or a bus, was something I always did. Rarely did I fall asleep, and as much as I always wished to be one of those kids whose parents got cars that had screens flipping down from the ceiling to play DVDs, it wasn’t my reality. But in a way, I was okay with that, because my eyes were constantly scanning the world out the window.

It wasn’t uncommon for me to try and directly replicate what I saw in the real world in my own world that I would create in my bedroom. I became very proficient at using those blocks, and sometimes even Legos, to build replicas, or at least influences of real-life buildings and homes. I would start hearing praises from my parents, mostly my mother who implanted the first affirmations of me becoming an architect. And then as I grew out of playing with children’s toys, things started to transform on paper.

In a way, my imaginary worlds never went away, rather I got to live them in the first person in my head. As I mentioned, I would play different scenarios of what my life would be like as an adult, often as an architect, but also in different ways. My dream jobs back then varied from being a comedian, to an affluent actor, even a lead singer in a band, to just simply thinking about winning the lottery. All these visualizations were challenged by a series of questions, one of which was, what would my home look like?

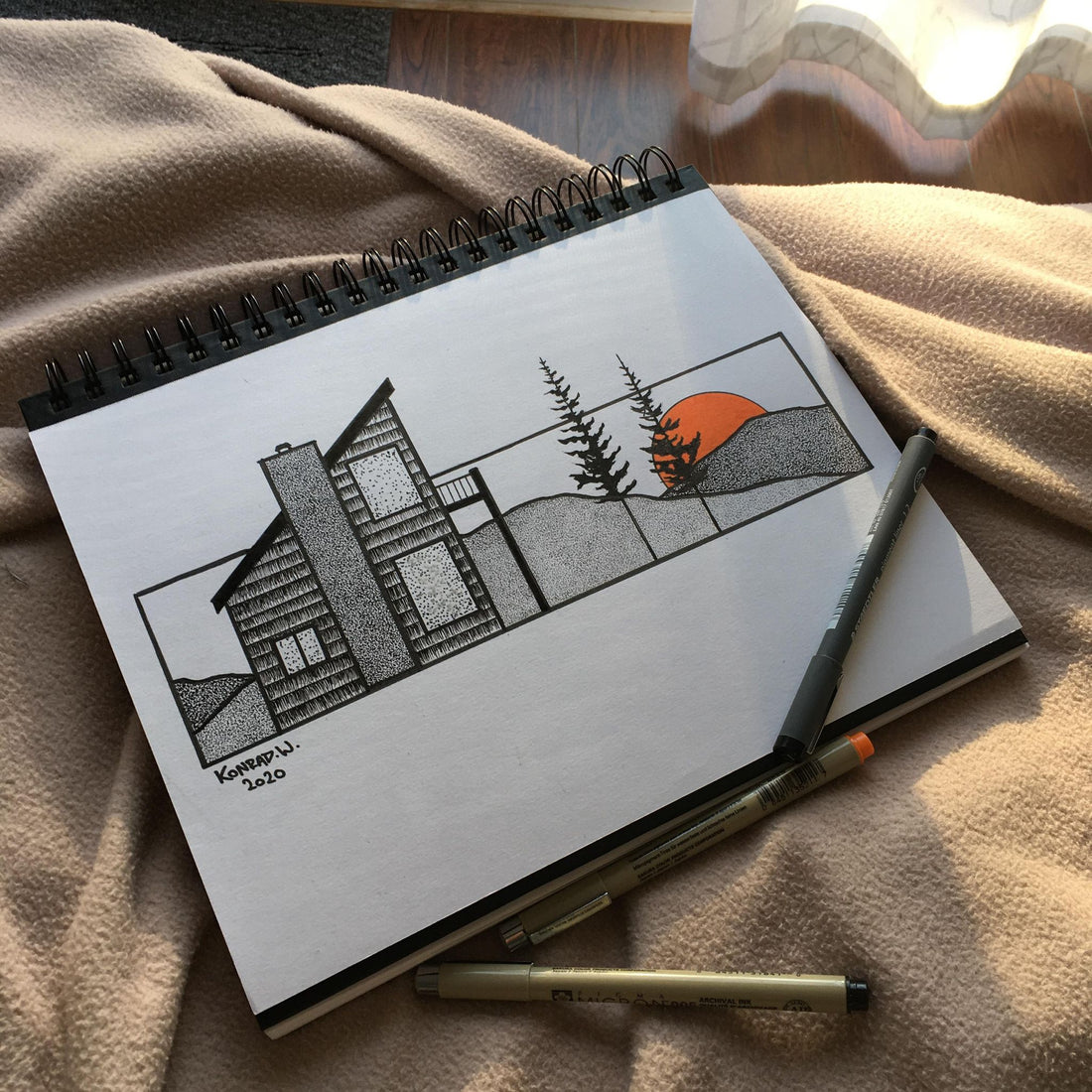

And so it began all in my head, in any downtime I had, usually on my long bus rides to and from school. Eventually, it was hard to fully visualize my thoughts, so I would draw them out. I would spend hours drawing the fronts and backs of houses, taking visual ques that I saw in the real world and emulating them into my own designs. Eventually I would get very precise, using a ruler and measuring things to make very detailed drawings of homes. They often would resemble what homes looked like if you went online and looked at custom home designs – something I found myself doing more of back then to gather inspiration. From there, I started to draw out floor plans of theses homes, making them super neat and precise as well, and even designing in furniture from the bird’s eye view perspective.

All of this helped it make it easier for me to dream of alter future versions of myself. Some would say that if I instead focused my energy in actually studying and trying to understand the physics and maths that these architectural schools want their students to know, then maybe I would have carved myself a real path into that field. However, no matter how drastically different it is to my artistic career today, these moments of play and dreaming were effectively working out my creative pathways in my brain. Creative pathways that are used to make illustrations for other people to enjoy.

Long gone are the days of me wanting to be a rockstar, and the stereotypical lifestyle that comes along with it, but when I look back at it all now, I can see how those early days have truly transpired into the creative being I am today. I’m very grateful for that, as it has opened up a world of possibilities that I could have never imagined. In those moments, I nor anyone else for that matter thought that I was preparing myself for a future in the arts. It was one of those things that was acknowledged heavily by my parents and peers that I was artistic, however being an artist back then, and to an extent still considered an unrealistic job today. An architect on the other hand, well that’s pretty realistic (sarcasm)

This is only one aspect of what has helped form Naturally Illustrated. Many years before it formed, the groundwork was being laid, and that’s wild to me. I have to end this by tying it back to architecture somehow but imagine digging a hole and building a foundation to a home well before you have any idea of what it will become. It’s unimaginable. Luckily, our careers and more importantly, our lives are not like constructing a house, rather they’re a mouldable, evolving and if we let it, a limitless opportunity to achieve greatness.